Making C-15 better.

When Parliament resumes sitting this week, C-15 will be back at Committee for a chance to improve the bill. Here are some suggestions for one of the more controversial sections of the bill.

Bill C-15 is the Carney government’s first Budget Implementation legislation. For the uninitiated, federal budgets don’t just change things like rates in the Income Tax Act or officially cancel the Digital Services Tax. There has to be legislation that puts the budget’s words into a legal instrument. Usually, it takes two implementation bills per budget and, while no government has been defeated on a vote on a budget implementation bill, I expect that the confidence convention for a minority government likely means that defeat of this legislation would be seen as tantamount to a motion of non-confidence.

But, governments can also accept amendments to legislation proposed at the Committee stage. In fact, I might argue it is good and right for Parliamentarians to do their job to improve government legislation when they have the opportunity, and governments should be open to advice and input from their Parliamentary colleagues.

As I’ve already said, there are some things in the omnibus bill that are good and much-needed public policy. But I also expressed some concerns regarding Div 5 of the bill, the section that makes major amendments to the existing Red Tape Reduction Act. It would create broad new executive powers to exempt designated persons, corporations, partnerships, or provinces, from any federal legislative or regulatory provision, other than the Criminal Code. You can read my previous post if you want a summary of this part of the bill.

I take it at face value that the federal government believes it must reduce regulatory burdens in Canada, as part of a whole-of-government effort to build new and more resilient economic relationships across the country and around the world. I start by looking at the evidence on Canada’s regulatory burden, relative to other countries, including some modeling from the same sources cited in the federal budget. Then I ask whether there was clear demand for the kind of legislative changes to The Red Tape Reduction Act that C-15 would make. Finally, I suggest some avenues to move forward that I hope might find support across party lines in Parliament.

Does Canada have a heavy regulatory burden?

The 2025 federal budget cites (see page 76) a 2025 Statistics Canada paper that uses econometric modelling to estimate the effect of cumulative regulatory burden on overall economic growth in Canada. That study adopts a new measure developed by Transport Canada and the consulting firm KPMG, which counted the number of regulatory requirements and used AI to estimate the incidence of these requirements across sectors of economic activity in Canada. This is different from just counting regulations, which is what the current text of The Red Tape Reduction Act directs the federal government to do with a supposed one-for-one rule to cap the growth in the number of regulations. You can read my previous post about the dismal track record of that legislation.

Side bar: Regulations have subjects (entities that have to comply with the regs) and objects (things those entities have to do to be in compliance). A government that makes regulations is required to implement them—which means education, investigation, and compliance enforcement, which means that regulations impose costs not only on regulated businesses, but also on governments (and therefore all taxpayers). The estimated cumulative effect of regulatory burden on economic growth is what the government cited from the Stat Can study, but I find it noteworthy that the same study finds that the count of regulatory requirements on government grew by 46% between 2006 and 2021, much faster than the growth in regulatory requirements on industry (37%) over the same period.

As the Budget accurately quotes, the Stat Can study estimates that the increase in regulatory requirements on industry over the study period (2006 to 2021) has been associated with a cumulative decline in GDP of 1.7% over the same period. The same study estimates that business investment in tangible assets (including construction) declines by about 0.06 percentage points for a 1% in cumulative regulatory requirements, after controlling for things like the size of the firm and cyclical factors. But, and this is important, the model only identifies changes in investment among firms doing any investing to begin with. That is, the impact is at the intensive margin, not the extensive margin: increases in regulatory requirements don’t seem to push firms that are investors into halting investment. Instead, additional requirements might just reduce what investment those firms are already doing by a little bit. In fact, another study has found that, particularly when firms look at their neighbouring peers, regulatory burden (alongside political uncertainty) can actually incent firms to invest more in research and development. This might not make sense until it does.

All administrative burden is relative, and firms have to weigh the costs and benefits of being where they are, compared to where they think they could go (in addition to all of the other ways that place is sticky). It has been the norm to evaluate Canada’s regulatory burden in comparison to the United States of America. On the one hand, we share a long border and have enjoyed a highly integrated market for decades. On the other hand, there is a lot, I mean A LOT, of very worrisome stuff going on in America right now. And as the Prime Minister himself recently pointed out, to much international acclaim, Canada generally enjoys (international interference efforts notwithstanding), a high degree of political stability, as well as predictability and transparency in our governance. Maybe, especially for larger established firms and their investors making medium and longer-term wagers, that stability and transparency might have value. But, in the current unstable geo-political environment, it is understandable that a Canadian government might not want to rest on laurels, but instead find ways to promote new sources of economic opportunity for Canadians. In that light, is there a case that Canada’s regulatory burden is too high and the kinds of measures in C-15 might be needed?

Maybe, but it depends on what you want out of deregulation.

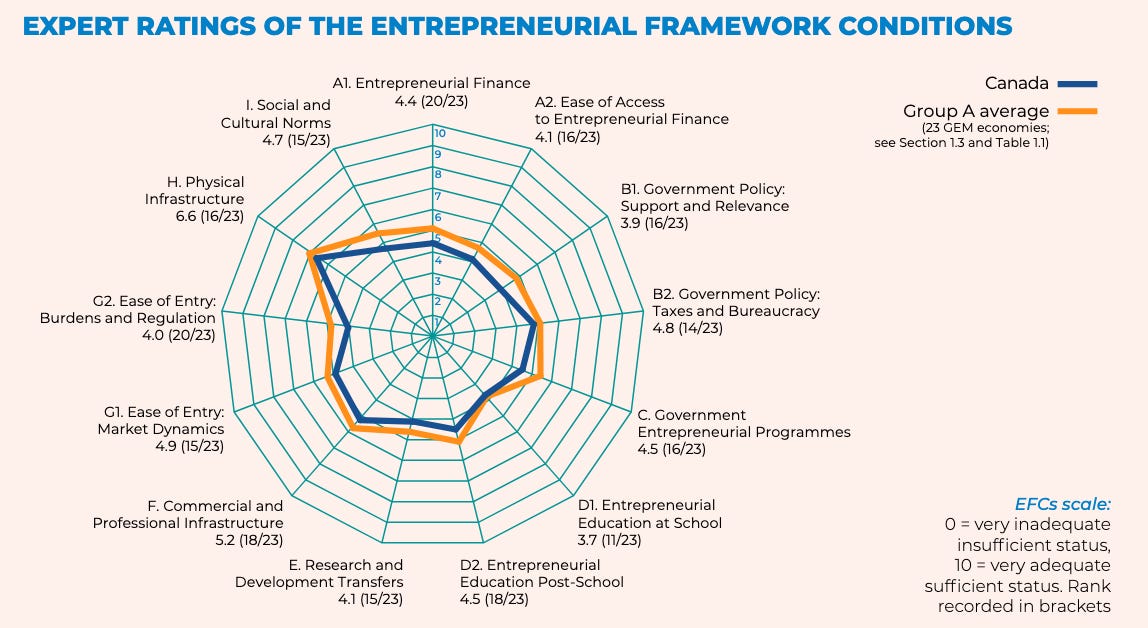

One perspective is that regulatory barriers for new entrants are too high, making it harder than necessary for entrepreneurs to launch and for some succeed. And in fact, one frequently-cited international benchmarking report on entrepreneurship notes that Canada’s regulatory barriers to entry are less conducive to new start-ups than comparable countries, though I note that “government bureaucracy” is not so much of a problem. However, a lot of new small businesses don’t make it, and not because the regulatory environment was the problem.

Another perspective is that regulation inhibits overall innovation and investments, particularly among established businesses, reducing competition and growth in the economy. This seemed to be more the line of thinking of the federal government in Budget 2025. In addition to the proposed legislative changes in C-15, the budget also committed to a major review of federal internal processes to streamline, delegate authorities, cut back on unnecessary or duplicative reporting, and cut down on the internal red tape of government (p.218). At the same time, the government seems to have acknowledged the need to make sure that administrative penalties and fines (one of the main tools for getting the subjects of regulations to comply) are meaningful and not just written off by non-compliant firms as a cost of doing business (p.218 again). That’s a more nuanced perspective on regulatory burden, and one we are told Budget 2026 will say more about.

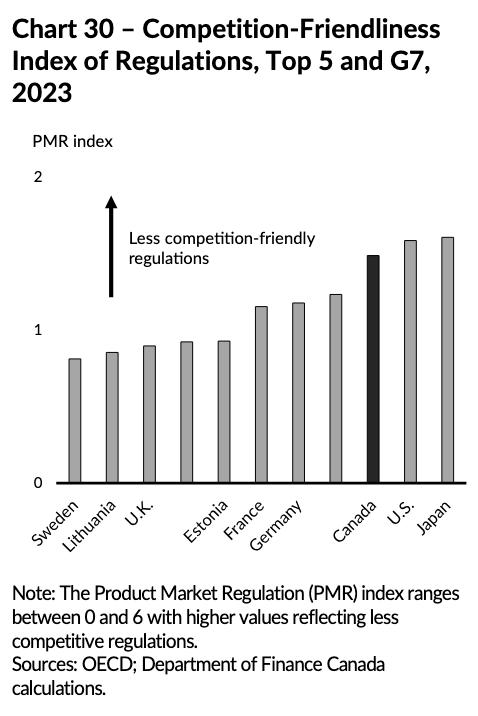

Now let me turn to the OECD data that is also cited in the Budget. In contrast to the Stat Can cumulative requirements approach, the OECD Product Market Regulation measures (on an annual basis, rather than cumulative) a wide range of regulatory barriers, both to new entrants and to greater competition, at both economy-wide and sector-specific levels. Chart 30 on page 55 of the 2025 budget reported on Canada’s overall PMR score, relative to other selected countries. I’ve included a copy of that chart below:

According to this data, Canada might want to look to European countries rather than the United States as comparisons to learn from. I would also note that when the OECD annual data are indexed to 2006, they suggest that Canada’s regulatory burden has been declining (which Stat Can reports in the same study cited above). I would also note that the PMR scales have a maximum value of 6, so take that into account as you interpret the Y-axis.

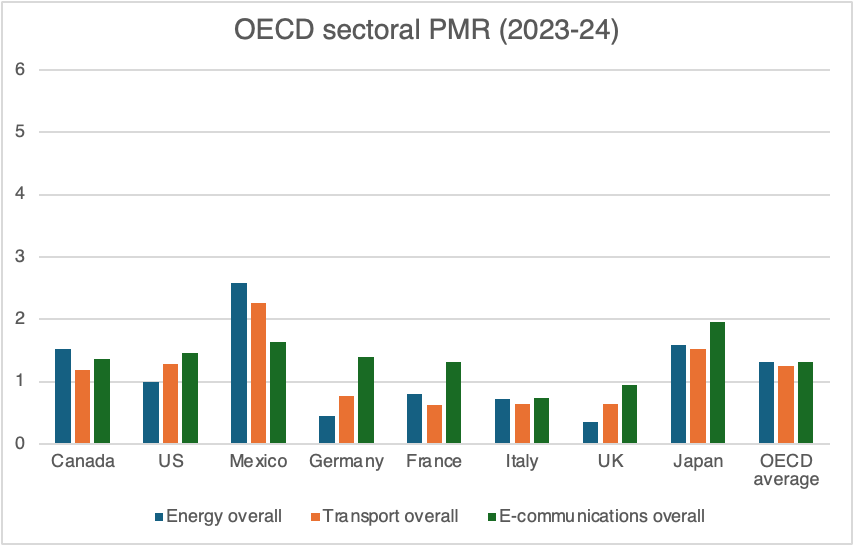

But what about the sectoral-level results? The OECD reports on regulatory stringency for each energy, transportation and telecommunications (they call it e-communications) sectors. Below is a chart I’ve generated, using the same 2023-24 annual PMR data, and compared to selected countries, but at the sectoral level. In this case, I’ve chosen G-7 countries, the OECD average, and Mexico, given that regional and sectoral comparisons seem to matter to investment decisions.

So, whether a government wanted to pursue smart deregulation to encourage new entrants or to encourage more innovation and investment, I think it’s fair to say that the international benchmarking data suggest there’s room for improvement, but maybe not an emergency that could otherwise tank Canada’s efforts to chart a new economic and geopolitical course.

Is there demand for what C-15 is offering?

I went back through the pre-budget consultation records to look for written evidence that there has been a constituency asking for the amendments to The Red Tape Reduction Act that C-15 is proposing.

The latest pre-budget consultations held by the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance received 948 separate briefs. I’m not currently able to see a copy of the traditional Committee summary and recommendations to the Government of Canada on the Committee website. In fairness, the Committee was under very tight timelines owing to a Spring election and a new fall budget target date.

Instead, I have gone through as many of the 948 submissions as I could manage with the aim of looking for evidence that there were documented calls for the flavour of deregulation that C-15 would offer. I did find voices keen on regulatory harmonization and deregulation more generally. Here’s a sample:

The Moving Economies Coalition (which includes the Mining Association of Canada, the Canadian Federation of Agriculture, Global Automakers of Canada, the Railway Association of Canada among others) called for “timely transparent, and predictable decisions for infrastructure, resource, and industrial projects,” but this took the shape of calling for clearer timelines, better coordination between jurisdictions in Canada, and more efficient public consultation processes.

Innovative Medicines Canada called for streamlining drug approvals in Canada, cross-jurisdiction coordination in pharmacare, and encouraged Canada to accept trusted foreign regulatory reviews as equivalent to domestic processes.

Food, Health and Consumer Products of Canada called on the government to mandate an economic lens for federal regulators, better cross-jurisdictional cooperation on drug products, separate regulations for prescription vs non-prescription drugs to enable risk-based approach, streamlining reviews of novel foods and food additives, and also suggested accepting assessments from trusted international regulators.

I suspect the Government of Canada may want to sidestep these calls for accepting “trusted” international regulatory reviews since we have regulatory cooperation agreements in place with the United States, and “trusted” requires stating which countries would qualify in a new federal policy.

FinTechs Canada called for financial sector regulators to adopt a mandate to promote competition.

The Council of Canadian Innovators made some sensible proposals on the main federal tax credit to support R&D (nicknamed SR&ED), like limiting access to only Canadian-controlled firms, and capping credits to avoid subsidizing zombie firms. But they didn’t pronounce on regulatory exemptions.

The Canadian Federation of Independent Business called for the one-for-one rule in The Red Tape Reduction Act to be turned into a two-for-one rule and that it be applied not just to regulations, but also to requirements in legislation and government policies. The CFIB also called for harmonized recognition of regulations across jurisdictions in Canada.

The Canadian Chamber of Commerce called for a new and mandatory economic competitiveness lens for federal regulators, interjurisdictional regulatory alignment and “eliminating red tape” more generally.

The Western Business Coalition called for regulatory excellence to be a priority and asked that the Government of Canada remove ministerial powers to designate a project for federal review, adopt a coordinated “one review” approach across jurisdictions, ensure that arm’s-length regulators make final decisions, not ministers, and it called for word and page limits on the amount of information a regulator can require. This generally seems pretty perpendicular to the text in C-15.

The Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters called for mandating economic growth as objective for federal regulators. Like the CFIB, it called on the government to “expand The Red Tape Reduction Act to include other compliance instruments such as legislation, policies, and guidelines to achieve more effective regulatory burden management and reduce the overall burden on companies.” The group also recommended that the federal government create a panel of industry and academics to review cost-benefit analyses of regulatory proposals, and that it use fiscal and other policy tools to incent interprovincial regulatory alignment.

I’m not sure that last one would past constitutional muster as a legitimate use of federal spending power, but let’s move on….

While there are a few of the submissions that point to The Red Tape Reduction Act as an instrument to expand, the calls are for a more general or horizontal (as in applying across the board to all subjects of regulatory burden) approach that would apply the one-for-one principle to more instruments, including laws and government “policy” (which I take to mean the more informal statement of interpretation or internal practices which are enabled by legislative powers). Again, the evidence on existing one-for-one rule is not great and the information/analytical requirements to expand reviews to other policy instruments may not be met by current systems.

There is also the published advice from the Treasury Board’s External Advisory Committee on Regulatory Competitiveness which issued a report in June 2024. It made a pretty sensible recommendation that the federal government invest in a public, digital and searchable database of requirements, including requirements from regulation, but also in legislation, “forms, guidance, and policy requirements”, which is likely a big but potentially very worthwhile endeavour. Not only could this help with transparency and certainty about red tape requirements, it might also help government and stakeholders identify priority areas for simplification and red tape reduction, along the lines requested by many of the business groups who took part in the pre-budget process.

The provisions that are in C-15 on regulatory and legislative exemptions do seem to be responding to demand from some voices for further progress on deregulation. But the text of C-15 goes much further than what business leaders have called for, at least publicly. There might well be wider demand for the direction that C-15 lays out that the government is aware of but that Parliament might not be.

But why would business leaders go on the record to call for this legislative change? After all, asking government to exempt you but not your competitors from a regulatory (or legislative or policy) requirement is tantamount to rent-seeking. Strategically, why would you do that out in the open of pre-budget consultations? Further, why would you call for that general power for the executive when you run the risk that the same executive might grant the exemption to your competitor, not you? As currently drafted, C-15 would take The Red Tape Reduction Act, a largely failed legislative initiative (in my analysis, again see this previous post), and turn it into something more like Gru’s free-ray gun.

The interests of businesses matter. The interests of the public, defined as inclusively as possible, matter far more.

How to move forward?

As of the time of writing, the Standing Committee on Finance has received just one written brief on the proposed amendments to The Red Tape Recuction Act contained in C-15. It’s from the Canadian Civil Liberties Association. The CCLA warns about several shortcomings in the legislation that it has identified: overly broad application to all sectors, too much flexibility for the government in publishing information on an exemption it granted and the reasons for it, the absence of a mechanism for Parliament to amend or revoke an exemption, and no requirement for consultations with other affected parties before an exemption is granted. But it doesn’t really make proposals for legislative improvements.

I started thinking about this blog with a view to suggesting the kinds of amendments that might address these and other concerns that have been levied. Amendments like:

limiting the application of the legislation to a list of specified sectors that the Governor in Council would publicly designate, in advance, as priorities for industrial policy, innovation, and national security;

But this would require that the government have selected, ahead of time, those sectors that would benefit and those that wouldn’t. That requires a heavy lift in analysis and some bets on where federal industrial policy ought to focus. As an October paper from the IMF notes, industrial policy can jump-start domestic production in targetted sectors, but it’s really hard to predict successful candidates in advance. Moreover, as the same paper notes, there’s no guarantee that sector-level gains will spill over into the wider economy. I could see a case for designating some sectors as critical for national economic security, not dissimilar to powers to designate some sectors as “vital” as proposed (again) in Bill C-8, also before the current Parliament. But then, the logic of C-8 is to scope some sectors into new requirements, not out of existing requirements. So I talked myself out of this route.

-or-

requiring that any Minister exercising powers under the law table in the House of Commons notice of an exclusion when a law of Parliament, or regulation required by a law, is at issue, within a set timeframe.

But, requirements to table in Parliament normally only apply to spans of days that Parliament is sitting. This could create perverse incentives for private firms and the executive to time exemptions to recess periods. Moreover, it shouldn’t matter if a notice has been formally tabled in Parliament or not - Parliament can and should hold the government accountable. I don’t know that C-15 needs an explicit mechanism, like tabling or referral to Committee, to ensure Parliamentary oversight. Those mechanisms, through order paper questions, oral questions, document requests, summons, Committee studies, and more are notionally already available to Parliamentarians willing to use them. But if the House, especially in a minority Parliament, were to pass a motion stating that an exemption granted by the executive was contrary to the will of Parliament, as expressed in its past legislative actions, then I don’t know how safe I would feel as an investor in a business that got a ministerial exemption. That’s definitely not a court case I would want to be party to. So I talked myself out of that route too.

-or-

introducing a requirement for consultation by the Government of Canada with interested parties before the effective date of any exemption authorized under C-15.

But the government cannot accurately identify all interested parties. That’s part of why, for example, the current regulatory process includes a mandatory publication (in the Canada Gazette) and consultation period. For many regulated parties, this is part of the very red tape they dislike. See, for example, the pre-budget submission from the Moving Economies Coalition. Proceedural fairness and executive expediency aren’t always aligned. On balance, in a democracy, it’s probably better to err on the side of proceedural fairness, especially if part of the value proposition you are offering is political stability, rule of law, and transparency in your public policy. So I talked myself out of that route too.

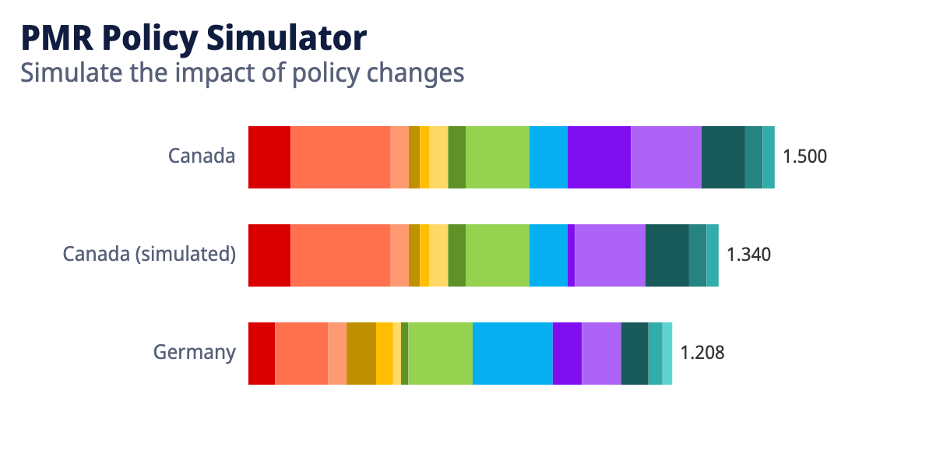

I don’t think that the drafters (government lawyers who work to translate a government’s policy direction into legislative form) did the government many favours in the way they wrote this section of C-15. Achieving the stated aim of encouraging “innovation, competitiveness or economic growth while protecting public health and safety and the environment” might be better pursued through other approaches. There are some good ideas (like the changes to SR&ED, and a more realistic definition of regulatory burden that isn’t about a count of regulations) in the published advice the Government of Canada has already received. There may also be some promising ideas to be found in the same OECD PMR data that was cited in the 2025 budget.

The OECD has used the data to create a policy simulator, allowing users to model selected policy changes for their impact on overall regulatory stringency, even relative to other countries. I used it to generate the chart below, comparing Canada’s current overall PMR regulatory stringency score to a hypothetical score, and in comparison to Germany. Why Germany? Well, it’s more in the direction the government seems to want to move (per their own budget chart) than the U.S.. Further, while Germany has its economic challenges, those seem to be more about excess output than Canada’s issues of operating below potential. There’s likely a happier middle ground to be found somehere.

Here’s what the simulator generated:

The simulator covers several different policy domains that might create red tape burdens on business entry and competition. I chose to run the simulation squarely focused on the kinds of national regulatory burdens that C-15 and current text of The Red Tape Reduction Act are intended to tackle. You can see the impact visually as the dramatic reduction in the dark purple section of the overal PMR score. This reflects changes like:

requiring government to publish a list of laws to be introduced, amended, sunsetted or renewed in the 6 months or so;

creating the public and digital inventory of regulatory requirements the TBS’s Advisory Group recommended, but also requiring that the data is regularly used to find opportunities for simplification;

creating a government-wide requirement that regulatory permit/licensing processes adopt a risk-proportionate approach, rather than a risk-averse approach;

introducing a “silence is consent” for some designated licenses and permits;

introducing a “tell us once” principle and enabling government bodies and regulators to more easily share information they have received.

Those measures would all move in a very different direction than C-15’s proposed changes to The Red Tape Reduction Act. This is beyond amendments to the BIA part 1. This would change, in pith and substance, the legislation as introduced. It would be a confidence issue, no doubt.

Rather than a standoff, my hope is that the government will agree to strike the relevant division from C-15 in exchange for a commitment by the FINA committee to return, quickly, with a study report on recommended legislative pathways to sustainably improve the federal regulatory environment to promote innovation, growth, competition while protecting public health and safety. That study might want to consider an option to repeal The Red Tape Reduction Act in favour of measures that will actuall work.

We’re in an economic war. It’s time for Parliament to act like it and find constructive ways to move forward, together.